Originally published in the Winter 2021 issue of Shrine Magazine, this essay commemorated the Parker centennial by reconsidering tropes of American musical tradition and genre in light of Parker’s unrealized artistic ambitions. It has since received minor revisions, in order to remain current to the time of its re-publication here.

Note to subscribers: This essay may be too long to be fully readable thru your email provider. To read the essay in full, visit the post on the Substack website.

"What happens to a dream deferred?"

– Langston Hughes, Harlem (1951)As abstract of a question as it may seem, the opening line of Langston Hughes’ 1951 poem Harlem has immediate impact in our present age. For a contemporary reader, that “dream deferred” is not so easily parsed from the Civil Rights movement that would ensue just a few years later, sparked by Earl Warren’s historic Brown v. Board of Education decision of 1954 and the brutal, unpunished murder of fourteen-year-old Emmett Till in 1955. Twelve years after Hughes penned his poem, Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. gave his immortal “I Have a Dream” speech, declaring how his children might live in a fairer and more just society—one day.

Today, nearly seventy years since the poem’s publication, many feel that the dream it enunciates is yet still deferred. Recent events in the United States—most notably the murder of George Floyd and the social and civil upheavals it sparked—have highlighted how the United States is yet to shake its racial animus, something that not only catalyzes such acute violence but that also perpetuates inequities in wealth, incarceration, health and safety. The words of James Baldwin redouble: how long is long enough to wait for the fulfillment of the progressive promise? To wait for deliverance from racism seems irresponsible if not impossible when the safety and well-being of one’s friends and family, one’s community, one’s fellow countrymen is imperiled.

Given the context in which most readers regard Harlem, using this poem to speak of music may seem inappropriate. But just because the arts seem insignificant compared to matters of life and death doesn’t mean that Hughes’ poetic imagination cannot give us insight into our cultural life.

As music enthusiasts around the world continue to celebrate the centennial of Charles “Yardbird” Parker (b. August 29, 1920), they would best honor the great saxophonist and artist not just through celebrating his achievements but also by looking to further his artistic and social aspirations. What many Charlie Parker fans do not know is that much of the Charlie Parker story has been left unwritten, that he achieved only a fraction of what he had hoped accomplish during his career. At the time of the publication of Hughes’ poem, Parker experienced numerous hardships that indefinitely deferred his artistic goals, leaving his dreams eternally unrealized upon his death in 1955.

In the couple of years preceding 1951, the world was Bird’s oyster. He was a recently minted star: favorable press coverage from the 1949 Paris Jazz Festival made him a hero back home, where he was the virtuosic ur-hipster of New York’s bebop counterculture. After his triumph abroad, Parker signed a new contract with Mercury Records, enabling him to make a series of commercially successful recordings: performances of popular songs with a small studio orchestra, records now known as the album Charlie Parker with Strings. That same year, a club named ‘Birdland’ in his honor opened on Broadway, just one block north of the famed 52nd Street. Parker began to settle into a happy and stable life in New York, working in the studios and clubs while starting a family with his partner Chan Richardson.

But the same year that his fame exploded, Parker confided in pianist Lennie Tristano that he had “said as much as he could” in the bebop idiom. As early as ’46 Parker had expressed interest in stepping away from his profession as a full-time performer in order to focus on composing, as he called it, “seriously”. By 1950, with his newly established celebrity and stability, Parker finally seemed ready to make good on his aspirations. But by the summer of 1951, when his dreams seem closer to being realized than ever before, everything began falling apart.

Caught by the authorities with narcotics in his possession, Parker had his cabaret card revoked by the New York State Liquor Board, meaning that he was barred from performing in the NYC clubs where he made his living. Stripped of his livelihood, Parker had to go on the road to support his family. Relentless travel, performing with inferior bands for unappreciative audiences, drug withdrawal, and separation from loved ones all deprived Parker of the time and mind frame necessary for compositional development.

By 1951, Parker was as well known for his pop records with strings as he was for his straight-ahead bebop quartet/quintet. Consequently, part of his touring package was playing with pickup string groups across the United States, splitting the bill between a straight-ahead quartet and an ensemble that approximated that of his Charlie Parker with Strings records. With the latter outfit, he’d perform those pop hits from the records—those canned arrangements, over and over again. What had initially seemed like an exciting first step towards greater artistic freedom quickly became a bore and an impingement upon his creativity.

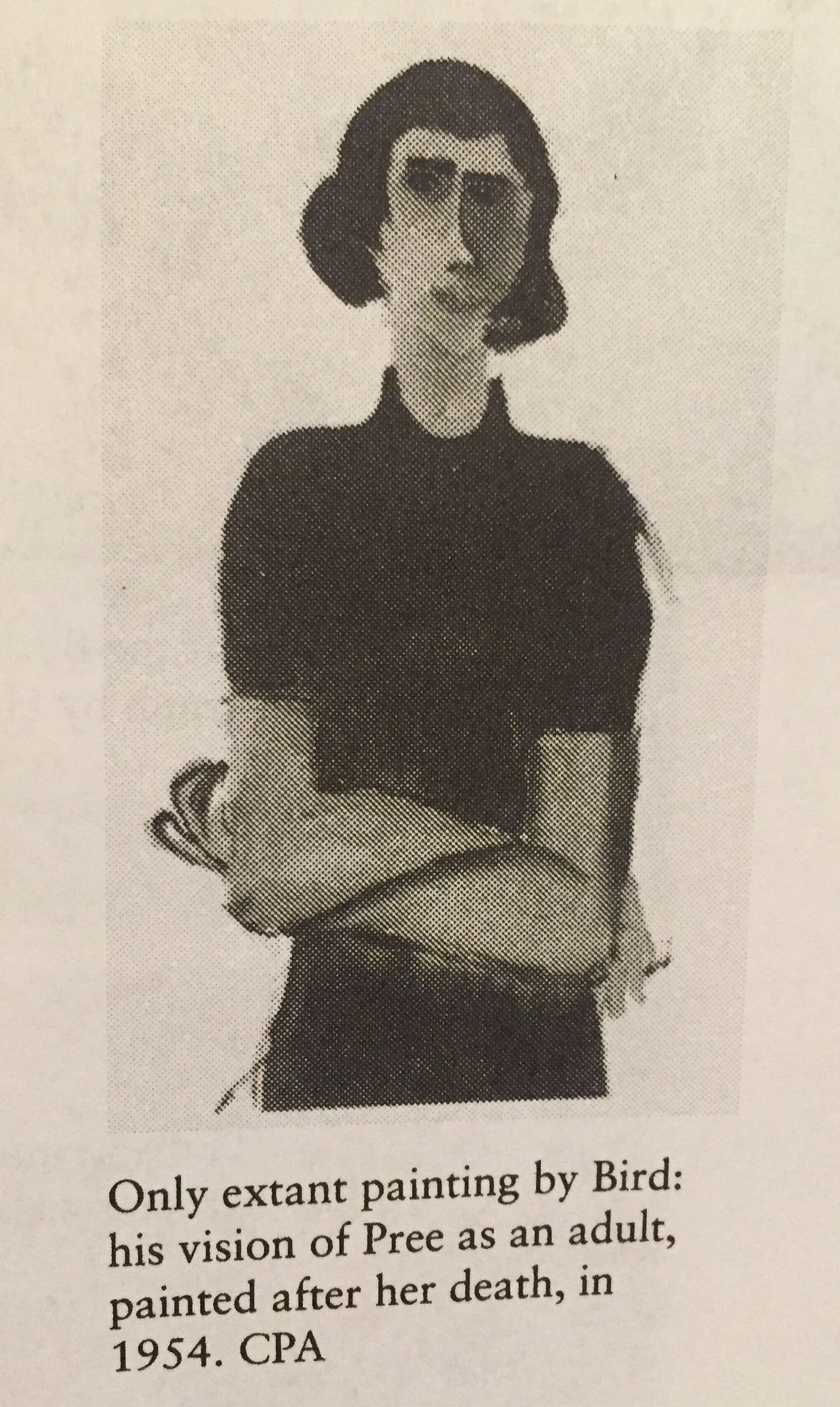

By the time Parker got his cabaret card reinstated in 1953, he was much worse for the wear: two-and-a-half years of incessant touring, paired with his disillusionment and debilitating health issues, left him in bad shape; his relationship with his booking agency became contentious, as they viewed him as unreliable; the whirlwind of touring and drug relapses had put a strain on his family life; and then, suddenly, his infant daughter Pree died. It was the final straw. Pree’s death sent Parker into a tailspin that culminated in his death only a year later. Musicians and hipsters martyrized Bird as the father of bebop and the king of the underground. But those who knew him well knew that he had desired so much more, begging the question: what exactly was Bird’s dream?

“the closest thing to classical music there is in the jazz field”

During a 1948 blindfold test with Leonard Feather for Metronome magazine, Charlie Parker surprised many of the magazine’s readers by demonstrating an appreciation for a range of musical styles, something unusual for a time when the jazz world was fiercely divided into several camps: the ‘moldy figs’ who relished the traditional music of New Orleans, the hangers-on from the Swing Era of the 1930s, and the modernists—the boppers—who claimed Parker’s music as their gospel. But what is even more insightful than Parker’s open-mindedness is his statement about one track in particular: Stan Kenton’s “Elegy for Alto”, an Ellington-esque experimental number featuring saxophonist George Weidler that utilized the standard big band instrumentation in a unique way: in the absence of a steady pulse from the rhythm section, the horns vacillate between murky, impressionistic accompaniment and an organized chaos. When asked to name his favorite record from the blindfold test, Parker named “Elegy for Alto”, for the following reason: “Kenton is the closest thing to classical music there is in the jazz field—if you want to call it jazz.”

What might’ve Parker meant by this? He offers no precise clarification of his stance in this particular interview. But elsewhere, Parker expressed his liking for another experimental Kenton cut: “House of Strings” from the album City of Glass. As someone billed as a ‘jazz musician’, Charlie Parker asserting his allegiance with music so unconventional in the jazz world was a bold claim. Stan Kenton occupied a unique position in jazz: he had both the resources and creative license to vacillate between radio-friendly pop hits and experiments like “Elegy for Alto”. The latter music, and the social/creative license it represented, was a far cry from Parker’s station in the music industry post-1949—as a jazz-pop crossover act, albeit hipper than most. By championing music as unusual as Kenton’s, Parker was challenging how he was labeled and affirming that his creative imagination was not beholden to his audience’s expectations or prejudices.

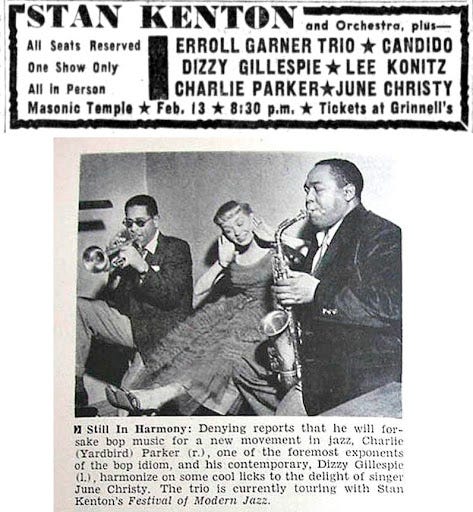

In 1954, Parker joined the Kenton Orchestra as a featured soloist for its Festival of Modern American Jazz tour. The music Kenton’s band played on this tour, however, was pop and bop favorites over which audiences expected to hear Parker—Night and Day, Cherokee, My Funny Valentine—all arranged and performed in a standard big band style. The tour was a grandiose commercial endeavor, designed to satisfy the bookkeepers (and Kenton’s ego).

Live recordings from the Portland Civic Auditorium in February of 1954 reveal Parker’s ineluctable brilliance, but anyone who knows Parker’s story knows how hard of a tour it must have been for him. Not only was he battling severe illness, he also must have felt increasingly disillusioned by his professional circumstances. The music industry had played its cruel joke on him once again: the closer he seemed to get to opportunities for playing new and exciting music, the more elusive those opportunities seemed to become. Such was the Sisyphean story of Parker’s creative life.

Bird’s “new movement”

Inspirations and missed opportunities

Through a mutual friend in clarinetist Tony Scott, Charlie Parker and composer Stefan Wolpe made each other’s acquaintance in the early 1950s. Wolpe, a German-Jewish expatriate by way of Austria and then Palestine, was a syncretic composer. A former pupil of Ferruccio Busoni and Anton Webern, he felt equally at home in Yiddish music, German singspiel stylings à la Kurt Weil, and Arnold Schoenberg’s serialism.

Bird saw in Wolpe a potential collaborator with whom he could make the ‘serious’ music he longed to play, so he floated the idea of commissioning Stefan to compose an orchestral piece that would feature Charlie as the soloist. Unfortunately, discussion was the extent of it. Bird’s producer, jazz impresario Norman Granz, would have none of such esoteric endeavors, and Wolpe may not have been all that enthusiastic about it himself. Over the next several years Granz would put the kibosh on many a creative endeavor, perpetually steering Parker towards what he deemed commercially safer ventures.

Seventy years later, we are left to wonder what a Parker-Wolpe collaboration might have sounded like. Perhaps Wolpe’s Passacaglia for Large Orchestra Op. 23 and his Konzert für 9 Instrumente Op. 22 can fuel our imaginations: Parker playing his angular melodies over Wolpe’s tense, kaleidoscopic ensemble passages.

In Parker’s own compositional endeavors, however, his musical taste veered away from the heaviness and discursive formalisms of Wolpe’s Viennese approach. While Parker did appreciate Schoenberg’s music, he generally favored a more vibrant manner of composition that had made its way from Europe to the United States during the wartime years.

Chief among such composers of Parker’s interest was the European musician most associated with him today, Igor Stravinsky. Most ornithologists know of Bird’s habit of traveling with scores of L’oiseau de feu and Le sacre du printempts, his predilection for quoting melodies from said pieces in his solos, and the apocryphal tale of him once doing so with such genius and élan that he startled maestro Stravinsky in the audience into spilling his drink. Bird spoke highly of Stravinsky as a composer and aesthetic inspiration on numerous occasions, and his desires to settle down and focus on composing while in Los Angeles in 1946 are said to be inspired by the Russian émigré’s residence there.

When asked about Hungarian composer Béla Bartók, Bird was apt to respond as he did in his 1953 radio interview with John McLellan:

He is my favorite. As far as I am concerned, he is, beyond a doubt, one of the most finished and accomplished musicians that’s ever lived.

Parker would rope many a friend into a Bartók listening session, an affair in which one could expect refreshments and incisive musical analysis. Both Bird and Bartók were transplants to New York City, but the Hungarian composer died in 1945 before Parker had a chance to make his acquaintance. One can only imagine what kind of epic listening sessions might’ve been shared by those two giants of music, had the stars aligned.

Then there’s composer and pedagogue Paul Hindemith, who had immigrated to Connecticut to found the Yale Collegium Musicum. Parker publicly voiced his admiration for Hindemith’s music throughout his career. He was particularly interested in the German composer’s Kleine Kammermusik Op. 24 No. 2, a five-movement composition for the standard wind quintet of flute, oboe, clarinet, French horn, and bassoon.

Parker spoke not merely in admiration of that piece but of wanting to write and perform music of his own that emulated it. Max Roach recalls Parker broaching such an idea with Norman Granz:

Bird had all sorts of musical combinations in mind. He wanted to make a record with Yehudi Menuhin and, at least, a forty-piece orchestra. He mapped out things for woodwinds and voices, and Norman Granz would holler, “What’s this? You can’t make money with this crazy combination. You can’t sell this stuff!”

Perhaps Bird persisted with Granz, because in May 1953 the producer booked a three-hour recording session for Parker’s quartet, a wind quintet, and a Dave Lambert-led vocal ensemble. Instead of utilizing Parker’s original sketches, arranger/orchestrator Gil Evans was recruited for the project. Bird simply instructed Evans to write like Hindemith’s Kammermusik but “not a copy”. This is the music that resulted:

Both Evans’ arrangements and Hindemith’s Kammermusik use wind quintet, sure, but otherwise they share no substantive similarities. None of Hindemith’s characteristic melodicism, harmony, rhythm, or orchestration is present in Evans’ pieces. The reasons for this could be manifold: Evans did not have much time to write the arrangements, they needed to be sight-readable at the recording session, the complex and idiosyncratic Hindemithian style was outside of Evans’ wheelhouse, and Evans was as beholden (if not more) to the wishes of Norman Granz who booked the session as he was to Charlie Parker. Hal McKusick, the clarinetist from the session, had a different perspective on the matter. But regardless of their cause, the results must have been infinitely frustrating for Bird—his creative dreams thwarted once again.

Bird’s vision…

All of this leads us to consider what Parker’s dream-music would have sounded like, and listening to the works of his three favorite contemporary composers (Bartók, Hindemith, and Stravinsky) has hopefully given us ideas. It should beg the question, what do these composers’ works all have in common?

The first major feature that all three composers’ works share is polytonality, in essence if not in formal technique. Polytonality is the simultaneity of multiple tonalities in a piece of music (as opposed to atonality, music that is uniform in its lack of tonal cohesion, or pantonality, the subsumption of all disparate harmonic information under a static, omnipresent tonic). Polytonality is most frequently understood as music in which different instruments play in different keys at the same time, or moments in which the harmony features complex sonorities based on the overlapping of distinct chords. I would expand this definition to include unprepared departures from or vacillations between one tonal center and another without the use of modulation or traditional voice leading, thus making the harmonies sound juxtaposed rather than interconnected. All of this verbiage may sound too technical for a non-musician or too liberal of a definition for music theorists, but what I mean to elucidate is simply a musical phenomenon whereby the typical tonal materials of harmony are juxtaposed in unconventional ways. The techniques used to achieve this effect not only result in compelling, sophisticated harmonic sonorities; they also create a sense of heterogeneity in an ensemble.

Reinforcing the heterogeneity within these composers’ works is their second most characteristic feature: their particular approach to orchestration. While all of these composers were capable of creating lush timbres and textures in the tradition of Wagner, they typically favored a more economical manner of combining sounds. In this leaner approach to orchestration, each part of a texture has a distinct timbre. The listener is thus able to distinguish each part from the others, and ultimately, able to more fully grasp all that goes on in a given moment. Such an approach to composition not only requires a talent for orchestration but also a thorough command of the polyphonic art of counterpoint, the weaving together of multiple melodies so that they agree with one another while remaining audibly distinct.

Both of these techniques—polytonality and a heterogeneous approach to orchestration—mutually reinforce each other, creating the vibrant dissonances characteristic of Bartók, Hindemith, and Stravinsky’s work. These techniques, paired with the composers’ strong rhythmic sensibilities, create music that has vitality and movement.

“Vitality and movement”—sounds like someone else’s music…

Speaking abstractly about these musical principles and techniques may help us understand why Parker regarded the music of Bartók, Hindemith, and Stravinsky as lodestars for his new vision: these features were already prominent in his own music.

Jazz musicians jump at the chance to explain how Bird’s solos outline additional chord changes that fit within those of the songs over which he played, plus how he would sometimes play substitute chords from distant keys. But such explanations ignore how Bird would do these things unexpectedly while playing with the band. If Bird played a divergent harmony that his accompaniment did not play, it would add a momentary polytonal flavor to the performance. Furthermore, the concept of groove in Parker’s bebop ensembles gave each band member greater freedom to do his own thing within the collective, resulting in a more heterogeneous group sound.

If the aforementioned elements were already characteristic of Parker’s music, then it stands to reason that he aimed to extend, elaborate, and refine (as Albert Murray might say) his own idiom, rather than try to assimilate into European classical or create an arbitrary fusion of genres. Parker substantiates this in the controversial 1949 Levin/Wilson interview for Downbeat:

He insists, however, that bop is not moving in the same direction as modern classical. He feels that it will be more flexible, more emotional, more colorful.

The closest Parker will come to an exact, technical description of what may happen is to say that he would like to emulate the precise, complex harmonic structures of Hindemith, but with an emotional coloring and a dynamic shading that he feels modern classical lacks.

Parker wanted to augment the sense of simultaneity in his music by widening its polytonal possibilities and expanding its palette of timbres. In order to achieve this, he intended to reconfigure the ensembles with which he worked, expanding their size and assimilating instrumentation traditionally used in European chamber and orchestral groups. But he was adamant that the size of an ensemble must not come at the expense of the rhythmic vitality and spontaneity of the small group sound he helped pioneer in the Forties. Even as he suggested in his 1954 interview with Paul Desmond that his ultimate impact would come through composing, Parker insisted that playing the saxophone would remain the focal point of his music: “I never want to lose my horn.”

Bird did not want his prospective orchestras or chamber groups to function as simple accompaniment or foils for his virtuosic flights, as we are accustomed to hearing on Charlie Parker with Strings; rather, he wanted to wholly integrate such instrumentation into his own musical idiom. But a major barrier to this development was the musicianship of ‘classical’ players themselves. Parker saw this musical language barrier as an obstacle to overcome, evidenced by his desire to work with violinist Ray Perry.

According to several musicians close with the two men, Parker had tried to recruit Perry for the Bird with Strings outfit as a featured soloist and member of the string section. Perry was a highly unusual musician for his time who played both acoustic and electric violin with swing and blues bands. If there was a violinist who played anything like Parker, Perry was the guy: a soloist with the harmonic inventiveness of Coleman Hawkins and Chu Berry and the rhythmic sensibilities of a Lester Young. He was one of those gigantic talents now relegated to the footnotes of history, but he commanded tremendous respect from his peers during his lifetime. Perry declined the offer to work with Bird in favor of a more lucrative offer to join the Illinois Jacquet Orchestra. Recordings with Sabby Lewis and Ethel Waters offer glimpses of Perry’s improvisatory prowess, leaving us to wonder what might have resulted if he and Parker had joined forces.

Besides Perry, Parker’s favorite ‘concert’ violinist was Russian-American virtuoso Jascha Heifetz. Teddy Blume, Parker’s former manager, recalled many an evening listening to Heifetz records with Bird:

He liked Heifetz so much. He used to say of him, “He’s the only man that screams. He’s got the greatest beat.”

It is hardly unusual or controversial to declare Heifetz your favorite violinist, but Bird’s reasons are telling. Parker often referred to his own playing or that of an inspired improviser as “wailing”, a term suggesting spontaneity while evoking the Blues sentiment in which his musicianship was steeped. And for a musician as rhythmic as Parker to praise Heifetz’s beat not only speaks volumes of the violinist’s rhythmic fluency but also suggests that such a rhythmic approach might be key for string players in Parker’s new music. Heifetz famously championed American works, both serious and lighthearted, alongside the classic European violin repertoire. His broad stylistic palette, fused with his unparalleled virtuosity, made his musicianship unmatched by concert violinists, both in his time and ever since.

As suggested by Bird’s comments about Heifetz and his desire to work with Ray Perry, it seems clear that in order for him to pull off the music he heard in his head he’d need to work with musicians who were capable of swinging, playing with blues inflection, and even taking improvised solos. But such players of symphonic instruments were hard to come by. In order for that reality to exist, he needed to manifest it, to create the kind of music that would steer potential collaborators in his direction, just as he and Dizzy Gillespie had done in the 1940s with their so-called ‘bebop’ innovations. We should understand Parker’s various failed or anticlimactic attempts at cross-genre collaboration (Charlie Parker with Strings, Stefan Wolpe, Gil Evans, Ray Perry) in this light.

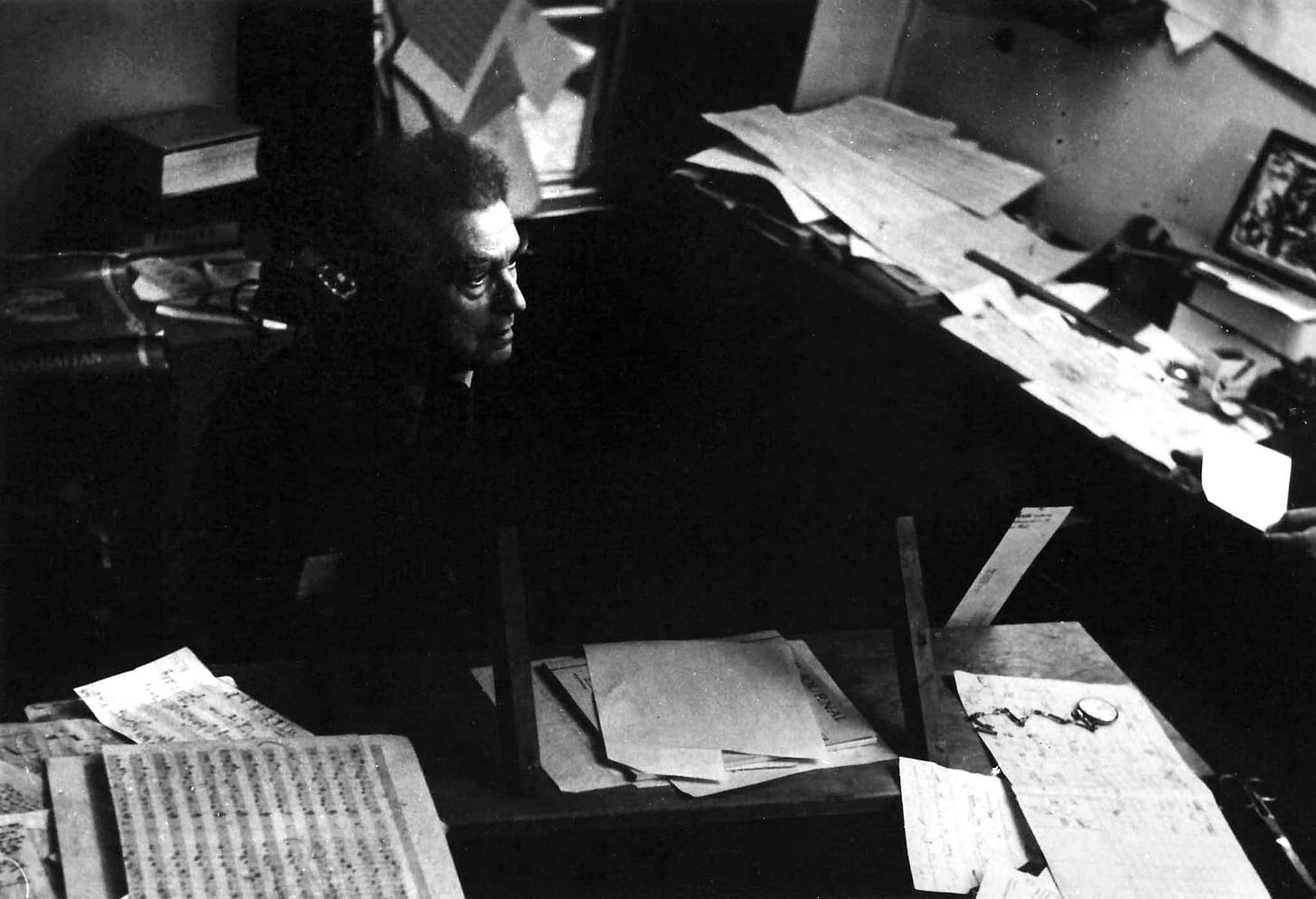

At the end of the day, Parker knew that he would have to compose the music that he’d want to play. No one else seemed to comprehend his vision. What Parker wanted to do was on the cutting edge of all music; it was not just some jazz novelty. Before striking out on this new musical frontier, Parker understood that he needed to hone new techniques, not just on his horn but also with paper-and-pen. In order to achieve his compositional objectives, Charlie Parker sought out a fellow enfant terrible of music: none other than Edgard Varèse.

Edgard Varèse

Parker must have seen in Varèse not only an artist of tremendous vision and craft but also a kindred spirit. The Frenchman perceived himself as belonging to a long line of French composers from Berlioz to Debussy, radical avant-gardists who experimented with the materials of music in order to alter the ways that their audiences experienced sound itself. During the Great War, Varèse moved from France to New York City, where he continued to conduct and compose. After the war ended, he chose to stay in New York, favoring the greater creative freedom and fresh inspiration that the city offered him, even though American classical music audiences were (as they still are) hyper-conservative. He was a groundbreaking French composer, endeavoring to take his musical tradition to unforeseen places while finding edification and inspiration in techniques, technologies, and traditions divergent from that of his continental peers.

Varèse had developed a unique approach to composing that must have been of great interest to Parker. Instead of constructing his music according to the Western holy tripartite of melody, harmony, and rhythm, Varèse approached the task of composition as “organizing sound”. The building blocks of his method were sound masses that he combined, juxtaposed, and moved around in musical space with rhythm and gesture. A complete master of orchestration, Varèse knew how to create arresting and energetic sounds that would wrestle with one another in his challenging compositions. His specialty was writing for percussion and wind ensembles.

Many Charlie Parker fans who know of Bird’s endeavor to study with Varèse don’t know what to make of it. On the surface, their musics could not be more different. But both musics contain tremendous visceral energy, and their complex, conversational approaches to musical organization avoid the long-windedness that had for so long bogged down composers after Beethoven.

As the saying goes, game recognizes game: Parker understood that Varèse could teach him much about the capabilities of chamber and orchestral groups that no one else could. Parker, the consummate individualist and a musical genius, surely would have done with these Varèsian lessons as he pleased, just as he completely reconfigured the Swing Era conventions under which his musical talents gestated.

* * *

In 1950, not only was Parker at a highpoint of his powers and his career, he also must have been hopeful for his future. One can hear this in the spirit of experimentation in his playing, exemplified on bootleg recordings from informal live performances, moments in which he would’ve felt most comfortable taking risks and trying new things.

On “I Didn’t Know What Time It Was” from St. Nicholas Arena, Parker breaks up his typical melodic flow. His sudden vacillations between playing ahead and behind of the beat, his interjected pauses, the asymmetry of his phrasing make his saxophone more gestural than ever before. If this new manner of playing might be any indication of the music he hoped to compose, then perhaps it presages the influence of one Edgard Varèse whose acquaintance he would make in the coming years.

On “Swivel Hips”, a number from a jam session at the Pershing Hotel in Chicago, Parker rearranges his musical vocabulary. It’s like William Burroughs’ Nova Trilogy: he cuts up sentences and paragraphs, pasting their fragments in unusual places over a familiar form (the form of “I Got Rhythm” instead of the pages of a book) in order to create new and exciting combinations. He tries some fascinating polytonal devices, more subtle than his characteristic tritone and semitone substitutions. Some things land, some don’t. Not everything is meant to. These recordings are Parker in the laboratory, working out postulates for a new theory of music-making.

Although not as well-known as the soloing for which he is legend, Parker’s voice in didactic composition was just as singular, personal, and mature, even if manifested in only a limited number of bebop head arrangements.

“Bird Feathers” exemplifies Parker’s distinctive melodic voice, while “Ah Leu Cha” is a rare demonstration of Bird composing in two-voice counterpoint. It is no small feat to develop a unique approach to melody, and it is even more unusual to develop a personal sound in the art of writing counterpoint. That Bird achieved both of these things within his limited pen-and-paper output shows how truly gifted and skilled he was as a composer.

But there is another facet of Bird’s oeuvre that is widely overlooked today, even by those who perform and cherish his repertoire. For many of his records, Parker would write a brief vamp to precede the main song form. These introductory moments, no more than just a few seconds at the beginning of a track, contain some of the greatest jouissance of his entire recorded catalogue. Often organized around a pedal point in the bass, these introductory vamps contain grooves of alacrity and dizzying polyrhythmic complexity. One can only imagine what the rhythmic vigor of the “Dewey Square” and “She Rote” intros would sound like through Bartók-esque string writing or Varèse-like timbres.

* * *

In 1954, the same year that Pree died, Edgard finally agreed to teach Parker. The lessons were to commence in the spring of 1955, upon Varèse’s return to New York from a trip abroad. But those lessons never happened. On the Ides of March, word hit the streets that Bird had left town, never to return.

Bird’s legacy and the history of American music

To examine the life of Charlie Parker is to examine a life of joys, victories, and history-altering achievements, but it is also to behold a life marred by tragedy, hardship, and disappointment. For an artist of Parker’s genius and influence to feel creatively stultified for nearly a decade (from 1946 to his death in 1955) is a prescription for personal and moral disaster.

Perhaps with the aid of a time machine, we could bring Charlie Parker here to the present where he could receive state-of-the-art medical treatment, effective addiction counseling, and grants that would allow him to focus on composing. That might enable Bird to write the music that he envisioned, but a written score needs to be played if it is to become music. If anything, the past seventy years of jazz and classical in America have made such music even more improbable today than it might have been in Parker’s day. But those barriers continue to stand tall because their foundations are deeply entrenched, tracing back to well before Parker’s lifetime.

“High Society”

What we consider ‘classical music’ in America didn’t really come to be in the United States until the mid/late 19th century. This development was part of a larger movement at the time that American historian Lawrence Levine chronicles in his seminal book Highbrow/Lowbrow. Through tracking the development of American theatre (-re, not –er), museums, concert halls and symphony orchestras, Levine elucidates the fundamental division between ‘high’ and ‘low’ culture in American society.

Perhaps the most interesting aspect of Levine’s book is its chronicle of Shakespearian theater in the United States, particularly during the 19th century when Shakespearean plays were immensely popular in the US. Shakespeare’s American popularity actually posed a problem for those of Catholic theatrical tastes, because the way in which Americans performed and watched theater was hardly genteel and diverged from contemporary performance practices overseas. Those who wanted to be considered highbrow (a term embraced by elitists at the time, referencing racist phrenology) needed an air of Europanismo, a culture of their own to distinguish themselves from the low, dirty, profane, ethnically-multiple American masses. Thus, there was a campaign to establish institutions (performance venues, subscription series, cultural criticism, academic departments) dedicated to the ‘proper’ performance and interpretation of the British bard. Over many decades of perseverance, the institutional approach to Shakespeare gradually became identified as the authoritative one and his plays fell out of favor with the American public.

The development of classical music in America had similar pretenses and methods but differed for a fundamental reason: European symphonic works have never enjoyed widespread popularity in the US. During the 19th century, American concertgoers tended to favor revues of shorter pieces over the longer symphonic works, and successful concerts tended to showcase a variety of styles and idioms: marches, operatic arias, popular dance numbers, et cetera. Concerts were hardly Americans’ preferred method of engaging with music: marching bands were the craze, as were social dances and amateur musicianship in the home and church.

Once again, those wealthy Americans who deigned to distinguish themselves via an exclusive culture of European connoisseurship wanted to create genteel spaces for the appreciation of certain European music that they deemed superior to the rabble of American cultural life. These patrons of the arts would band together to create institutions such as the New York Philharmonic (1842) and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra (1891), financial sinkholes well worth the investment for those who sought a distinguished aesthetic and social experience.

Am I glad that in the 21st century I can go to a concert hall and hear a Beethoven symphony performed in its entirety? You bet. But the unfortunate outcome of this particular ‘philanthropic’ endeavor is that it cultivated a false binary of cultural value in the United States: that which was co-signed by the concert hall was deemed the veritable high art, while all other music that was happening in the US was degraded as the detritus of American diversity and liberty.

In order to cultivate musicians to populate these symphony orchestras, American conservatories were established to specialize their students in playing this ‘highbrow’ music. In the eyes of its cultural elites, the United States would make its mark by out-Europe-ing Europe. But in order to ultimately achieve this, highbrows realized that American classical could not just be a Three B’s Hit Parade. Ultimately, the US would need to produce its own composers to write music in this esteemed European vein.

The paradox, however, was that such music had to sound distinctly American while conforming to the restrictions placed upon it by these wannabe European aesthetes. How to achieve this was the cause of much consternation and theorizing in the American musical establishment, quite to the confusion of European composers who visited the United States from abroad.

“a noble heritage in music”

In January of 1928, Maurice Ravel—hailed as France’s greatest living composer—undertook an extensive national tour of the United States. During this historic visit to America, Ravel took the opportunity to not only make the rounds with the American classical establishment but also to hear local music wherever his journey took him. In April, at the penultimate stop of his 21-city tour, Ravel gave a lecture at the Rice Conservatory of Music in Texas, where he discussed the issues that, in his mind, preoccupied contemporary music.

Ravel’s central interest in his lecture concerned national traditions in music. Now before you all jump on Ravel’s case for being another miniature Frenchman preoccupied with flaunting his national superiority, know that Maurice found much of intrigue and admiration in the music of foreign nations (of course, he couldn’t help ribbing the Germans a little). As much as Ravel was proud to be a French musician, he delighted in living in a cosmopolitan world in which he could enjoy and learn from traditions other than his own, and he understood that part of his artistry as a Frenchman was to explore his particular relationship to this expansive modern world around him.

Given his prestige and his interests, Ravel could not have been a more perfect specimen to give a lecture at one of the most prestigious conservatories in a United States that apparently still needed to find and establish its own national music. But at the end of his lecture, polite little Maurice dropped a bomb on the audience:

In conclusion I would say that even if negro music is not of purely American origin, nevertheless I believe it will prove to be an effective factor in the founding of an American school of music. At all events, may this national American music of yours embody a great deal of the rich and diverting rhythms of your jazz, a great deal of the emotional expression in your blues, and a great deal of the sentiment and spirit characteristic of your popular melodies and songs, worthily deriving from, and in turn contributing to, a noble heritage in music.

Whoa…

The audience of American musical literati at Rice was likely unprepared and certainly displeased to hear their esteemed guest say such things. The very elements that Ravel enumerated as fundamental to American music were all ‘lowbrow’ music that institutions like the conservatory at Rice were established to be fortifications against. What’s more, Ravel identified this foundational trinity with “negro music”. I don’t need to explain why that would have upset the American highbrow establishment…

I’d be remiss to ignore how Ravel made George Gershwin’s and Paul Whiteman’s acquaintance during his American tour and that the French composer complimented Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue. But I think musicologists generally overblow this fact while glossing over Ravel’s statements from his lecture. In speaking of other nations’ musics, Ravel cited numerous composers. Surely he would have mentioned Gershwin by name if he heard the young man’s work as a lodestar for American music. But he did not mention Gershwin, nor did he mention Whiteman. He mentioned “negroes”.

Rumor has it that Gershwin took Ravel to the Cotton Club in Harlem, which begs the question: Did Ravel hear Duke Ellington and his Orchestra?

Ravel was not the first prominent European composer to praise Black American music and suggest how the American musical establishment could stand to benefit from embracing it. During his three-year stint as director of the National Conservatory of Music in New York City, Czech composer Antonín Dvořák famously wrote: “In the negro melodies of America I discover all that is needed for a great and noble school of music.” But Dvořák’s statement differs greatly from Ravel’s. Dvořák seems to encourage the incorporation of folk melodies (such as those of the spirituals) into the extant European symphonic idiom. Such a device had been a trope of European music since Haydn’s time, seen as the means of ‘legitimizing’ folk music (by removing many of its characteristic features, of course). Ravel, on the other hand, speaks not of melodies to be cut-and-pasted into otherwise vaguely European music; rather, Ravel speaks of musical technique and, even more fundamentally, “expression”, “sentiment and spirit”.

Ravel’s statement suggests that not only did he hear the music of Black Americans as identifiably American but that he heard it as quintessentially American, that the very essence of American music could not be parsed from the Black American musical traditions that the establishment had always denigrated as illegitimate. Furthermore, Ravel acknowledges that this “noble heritage in music” had existed for some time, that ultimately a truly legitimate “American school of music” would be practically indistinguishable from it (“deriving from, and in turn contributing to…”).

What I personally find intriguing about Ravel’s closing remarks at Rice is the resemblance they bear to Albert Murray’s statements that there are three core elements that qualify jazz: 1) swing, the rhythmic feel and how musicians play together, 2) the Blues, the lyrical/expressive idiom borne out of the experience and spiritual comportment of a people, and 3) a commitment to the moment, spontaneity. The first two elements quite obviously correlate with what Ravel enumerated, but so does the third: since a musician’s improvisation/composition is always in relation to the form with which she is working, the spirit of her musical invention is always linked with the forms that are its basis.

There are ongoing discussions (read Nicholas Payton’s On Why Jazz Isn’t Cool Anymore and other essays) as to what it means to “swing” or tap into the Blues, as well as whether such attributes would solely characterize a genre known as ‘jazz’, or if the word ‘jazz’ is even appropriate for describing such a tradition. Personally, I wonder how Ravel, a musician and an outsider, perceived this music as constitutive of American music writ large, just as Ravel’s compositions exemplify French music. It provokes one to consider how these great so-called ‘jazz musicians’ perceived themselves, not only in relation to that term but also in relation to their heritage, how they conceived of heritage, tradition, and place in the world of modern music.

“it comes from everything of the finest-class music”

In 1938, pianist and composer Jelly Roll Morton gave a series of interviews with Alan Lomax for the United States Library of Congress. Now known as The Library of Congress Recordings, these interviews were Morton trying to ‘set the record straight’ about jazz, a music that he hyperbolically claimed to have invented:

Jazz music is based on strictly music. You have the finest ideas from the greatest operas, symphonies, and overtures in jazz music. There’s nothing finer than jazz music because it comes from everything of the finest-class music. The fact of the matter is, every musician in America had the wrong understanding about jazz music.

Many see this statement as an attempt to jettison derogatory connotations from jazz. As the self-proclaimed “originator of jazz”, Morton likely intended this. But never does he, a Creole man from New Orleans who worked primarily with Black and Creole musicians, obscure the importance of the Blues and ragtime in his music. His music had those “rich and diverting rhythms” and that “emotional expression” that Ravel had so admired and American elites saw as a ‘pernicious Negro influence’ on American society. What’s apparent is that Morton made no arbitrary distinction between high and low culture – if it made for good music, Morton incorporated it into his own. He lived in New Orleans at a time when the Crescent City was one of the most cosmopolitan cities in the world. He had access to many different idioms of both foreign and homegrown music that would shape American culture, in turn influencing how he would do so himself.

Despite its diverse influences, Morton’s music hardly sounds pastiche. It is cosmopolitan, for sure, but it always has a singular voice. Another Morton quote from the Library of Congress Recordings is telling:

Jazz music is to be played sweet, soft, plenty rhythm. When you have your plenty rhythm, with plenty of swing, it becomes beautiful.

Insofar as art aspires to beauty, it is fair to assume that that which evinces ‘the beautiful’ in an idiom is its most fundamental element. For Morton, such technique is “plenty rhythm, with plenty of swing”, an element that admirers and detractors alike attributed to Black Americans (that Sidney Bechet specifically attributed to the practices of enslaved persons in New Orleans’ Congo Square during the antebellum years).

Jelly Roll Morton was hardly unique in refusing to kowtow to the arbitrary highbrow/lowbrow distinction: Duke Ellington, for example, fiercely championed his music that was of and about Black American heritage while refusing to categorize himself and his music according to the unmusical partitions of the music world.

Charlie Parker belongs with this tradition of music in America. If the preceding seven thousand words have not convinced you, then read a few of Parker’s own—his closing remarks from the 1948 Metronome blindfold test, regarding the notion of ‘jazz’:

…as far as I’m concerned, there’s no such thing; you can’t classify music with words—jazz, swing, Dixieland, et cetera. It’s just different forms of music; people have different conceptions and different ways of presenting things. Personally, I just like to call it music, and music is what I like.

Reification thru deification

As much as the Ravels and Dvořáks of the world may have admired Black American music, American music institutions—from the entertainment industry to the ivory tower—denigrated both Black people and their music as other. Parker’s desire to investigate techniques practiced by European immigrants Bartók, Hindemith, Stravinsky, and Varèse for his own musical expression was met with confusion and ire. Today, seventy years later, we’d like to think of our society as more informed and open-minded than pre-civil rights America. But even if people today recognized Parker’s musical vision, actualizing it would be just as improbable—likely more so—in our time than in Parker’s. The institutions that encumbered Parker’s creativity are even more entrenched today, thanks in part to Parker’s cult of celebrity following his death in 1955.

From the moment that Jay McShann’s “Hootie Blues” hit record stores in 1941, Bird had emulators and copycats. After he and Dizzy Gillespie pioneered their new music in the mid-1940s, practically everyone seemed to follow suit with their approach to small ensembles. But this fixation on the Parker brand of jazz as gospel acquired unprecedented degrees of rigidity and orthodoxy as jazz finally gained a footing in the arts institutions that had for so long denigrated it. Replete with its traditionalists, formalists, and myopic ‘innovators’, this new brand of institutional jazz defined Parker’s music and legacy as a narrow set of conventions. Not only did this circumscribe the creative vision of those in jazz, it also legitimated American classical musicians’ ambivalence to music outside of their narrow world as well: They [jazz] are their own thing. See? We’re just fundamentally different genres of music.

After WWII, American classical institutions became increasingly austere. Concert programming increasingly fetishized ‘the long 19th century’ of European masterworks while avant-gardists (self-appointed as “New music”) became increasingly abstract. The former effort, actually enjoyable for some people without a music degree, continually ingrained the idea of faux-European ‘tradition’ in America, while the latter bolstered the academy’s claims to ‘objective’ musical knowledge (a claim that is presently transmuting into the classical/New music establishment’s embrace of contemporary identity politics, critical theory, and the social sciences).

The growth of institutional arts as extracurricular activities for American youth has imprinted these jazz and classical mindsets on more young people than ever before. The result is that many of the most capable musicians in America today came through these institutions, normalizing these genres’ estrangement from each other and everyday people. We are led to believe that this is simply the natural order of things in music.

Meanwhile, American classical music is concerned with how to rectify its attendant racism, sexism, and classism. The popular solution seem to be inclusivity: programming the symphonies of Florence Price, William Grant Still, and contemporary composers of color; creating new music theory textbooks that feature excerpts from more diverse musicians; and fostering more diverse orchestras and student bodies at conservatories. Worthwhile as these endeavors may be, none of them challenge the fundamental methods and highbrow pretensions that alienate classical music and its musicians from American cultural life. Such reform legitimizes the old highbrow way of doing things, always obsolete but now grasping at straws in order to remain relevant with a diversifying upper-middle class.

Seventy years since Parker spoke of his dream, American symphonic instrumentalists still can’t swing and jazz musicians create a compelling case for why one shouldn’t want to. Even as American jazz and classical institutions become increasingly ethnic- and gender-diverse, they still function under a separate but equal paradigm grounded in historical misunderstanding and exclusionary music-making.

Contemporary crossings

Since its commercial success in the 1950s, Charlie Parker with Strings has become the mold for a particular kind of ‘cross-over’ music. From Clifford Brown with Strings to Miles Davis’ legendary collaborations with Gil Evans, most “with Strings” or ‘orchestral’ projects have had one thing in common: the orchestral/chamber group and the band are treated as two different ensembles, each fulfilling its distinct role: the band, usually fronted by a soloist, grooves et cetera, while the other ensemble plays simple accompaniment. Rarely is there interplay between the two groups. (Ironically, one of the most successful examples of a soloist and string ensemble’s interplay is Stan Getz’s Focus, on which Getz overdubbed most his solos.) But in circumstances of live recording or performance, this bifurcation of the ensemble is the efficacious way to pull off a successful venture with musicians of different idioms: you play to the two groups’ strengths, foreclosing the possibility of their interaction or integration.

Many musical luminaries of our day, celebrated instrumentalists/bandleaders/ composers like Parker, have taken on the behemoth task of incorporating chamber or orchestral instrumentation into their own music.

Notable examples include Wynton Marsalis (Swing Symphony, All Rise), Nicholas Payton (Black American Symphony, Sketches of Spain), Chris Potter (Imaginary Cities), Wayne Shorter (Without a Net, Emanon), Esperanza Spalding (Chamber Music Society, Radio Music Society, 12 Little Spells), and Miguel Zenón (Alma Adentro, Yo Soy La Tradición).

With this embarrassment of riches, perhaps it is as good of a time as ever to revisit Parker’s aspirations. Some of the aforementioned musicians are probably unconcerned with speculations about Parker’s unrequited art while others may see themselves as torchbearers of the Parker tradition. Regardless, all of them took an ambitious plunge by making the music that they wanted to make, for which they deserve commendation.

* * *

As arbitrary as ‘big anniversaries’ can be, Charlie Parker’s centennial has been cause to celebrate and reflect on his legacy. Central to his legacy is the extensive discography he left behind, as well as the impact he made on his contemporaries. Those of us who care about Parker’s music should therefore continue to cherish the recordings and support his living legacy in torchbearers such as Roy Haynes, as well as their acolytes. But I’d also like to humbly suggest something more:

It behooves us to deepen and broaden our imaginations beyond the provincial confines of how the American music establishment categorized Bird and categorizes us.

Remember…

There is a difference between principles and dogma, technique and a pigeonhole.

In 2022, we don’t need imagination to know what happens to a dream deferred. But perhaps poetic imagination could help us actualize such a dream…

And if such actuality goes against the grain of music as we understand it, then so be it. As a wise man once said:

They teach you there’s a boundary line to music, but, man, there’s no boundary line to art.

Here’s to another one hundred years of Bird, an era of art, a century in which we may realize that imagination is for much more than dreaming.

Bird Lives!

Sources

Bechet, Sidney. Treat It Gentle: An Autobiography. 2nd ed. Da Capo Press. New York, NY. 2002.

Gitler, Ira. Swing to Bop: an Oral History of the Transition in Jazz in the 1940s. Oxford University Press. New York, NY. 1985.

Jelly Roll Morton: The Complete Library of Congress Recordings by Alan Lomax. Rounder 11661-1889-2 (8 CDs), 2006.

Levine, Lawrence. Highbrow/Lowbrow: The Emergence of Cultural Hierarchy in America. Harvard University Press. Cambridge, MA. 1988.

Murray, Albert. “Part Four: The Ellington Synthesis.” The Blue Devils of Nada: A Contemporary American Approach to Aesthetic Statement. Vintage Books. New York, NY. 1996.

Murray, Albert. Stomping the Blues. Anniversary, Reprint edition. University of Minnesota Press. Minneapolis, MN. 2017.

Parker, Chan. My Life in E-Flat. University of South Carolina Press. Columbia, SC. 1993.

Ravel, Maurice, 1875-1937. “Contemporary music.” Rice Institute Pamphlet – Rice University Studies, 15, no. 2 (1928) Rice University: http://hdl.handle.net/1911/8425

Reisner, Robert. Bird: The Legend of Charlie Parker. Da Capo Press. New York, NY. 1962.

Russell, Ross. Bird Lives! The High Life & Hard Times of Charlie (Yardbird) Parker. Da Capo Press. New York, NY. 1973.

Schaap, Phil. “Bird’s Eye Preview of Third Stream I-V.” Bird Flight. Broadcast by 89.9 WKCR-FM NY. 1/28-2/8/2016. Archived at https://www.philschaapjazz.com/sections/bird-flight

Woideck, Carl. Charlie Parker: His Music and Life. The University of Michigan Press. Ann Arbor, MI. 1998.

Great!